On this page we will be reporting on our funded projects as they progress, and as they come to fruition.

- ‘Countermeasures: Giving children better control over how they’re observed by digital sensors’, Angus Main (RCA).

- ‘Zoom Obscura: Creative Interventions for a Data Ethics of Video Conferencing Beyond Encryption‘, Pip Thornton (University of Edinburgh) et al.

- ‘Data and Disadvantage: Taking a Regional Approach Towards Human Data Interaction (HDI) to Inform Local and National Digital Skills Policies’, Professor Sarah Hayes (University of Wolverhampton) et al.

- ‘MIRLCAuto: A Virtual Agent for Music Information Retrieval in Live Coding’, Dr Anna Xambó, (MTI2/De Montfort University), in partnership with IKLECTIK, Leicester Hackspace, l’ull cec and Phonos

- ‘Governing Philosophies in Technology Policy: Permissionless Innovation vs. the Precautionary Principle’, Vian Bakir (Bangor University) and Gilad Rosner (IoT Privacy Forum)

- ‘ExTRA-PPOLATE: (Explainable Therapy Related Annotations: Patient & Practitioner Oriented Learning Assisting Trust & Engagement)’, Mat Rawsthorne, Jacob Andrews et al.

- ‘BREATHE – IoT in the Wild’, Professor Katharine Willis (University of Plymouth) et al.

- ‘Rights of Childhood: Affective Computing and Data Protection‘, Prof A. McStay (Bangor University) and G. Rosner (IoT Privacy Forum).

‘Countermeasures: Giving children better control over how they’re observed by digital sensors’, Angus Main (RCA).

Thus far, our themes and responding projects have focused on the conceptual framework for system design that HDI offers us, centred on the three tenets of legibility, agency and negotiability for the user. But what happens when one has understanding of the data, but cannot change the system or work positively with those behind it? Data processing in these forms becomes more akin to surveillance. When legibility, agency and negotiability are not enough then, the need for a fourth tenet, resistance, emerges. In response to our eighth theme ‘Surveillance/Resistance’, Angus Main’s Countermeasures project aims to research into children’s awareness and attitudes towards surveillance, and to enable them to block or subvert sensors in digital devices they use.

This project involved a range of academics and industry professionals; Angus Main (PI, RCA), Dr Dylan Yamada-Rice (Co-I, RCA and Dubit), Deborah Rodriguez (Co-I, CEO Gluck Workshops), Professor John Potter (UCL) and Professor Steve Love (Glasgow School of Art). It was also born out of the PI’s previous project, which resulted in a toolkit for adults to disrupt sensors in smart devices.

Sensors in our electronic devices are increasing drastically in both amounts and sophistication (the original iPhone in 2007 contained 3 sensors, whereas the latest in 2021 contains around 20). Surrounding you now, there are most likely a number of devices observing you with sophisticated microphones, cameras, GPS, accelerometers and gyroscopes (motion sensors), recording physical behaviours, such as your voice, facial expressions, and pulse rate. Previously innate objects like TVs, doorbells, watches and speakers are becoming equipped with theses sensors, forming an Internet of Things (IoT), a network of smart objects capable of sensing us. We may be aware of some of these sensors through the functionality of certain devices. We may be less aware that technology companies use many of these sensors for more than our intended use, to passively collect data on us. This data enables machine learning and AI to infer information about us, and to make predictions about our preferences and behaviours, providing a customised, often ‘magical’ experience for the user. But it is simultaneously a form of pervasive surveillance, capable of building complex personal profiles of individuals and their tendencies.

Issues of surveillance are complicated further when we are dealing with children, who in many cases will not be aware of sensors or their capabilities, and are too young to understand or legally sign terms and conditions agreements (13 often being the age of legal consent for many digital devices and platforms). Yet children are still often users of devices equipped with sensors, such as phones, tablets, games consoles or TVs, or are in home environments where such devices exist. One use of children’s data collected by technology companies from such devices is to inform the development of future products for children. Not only does this quantitative form of data gathering erase children’s voices, but it is in direct contradiction with the UN Convention (1989) on the Rights for Children, which states they should be able to voice their own opinions on matters that affect them.

Countermeasures aimed to gain insight into how children (specifically aged 8-12) perceive the sensing and data collecting capabilities of their digital devices, as well as how attitudes towards digital sensing affect their exposure to surveillance. Via a series of co-design work packages with children, the project also aimed to explore practical methods of sensor blocking and disruption, informing children’s attitudes towards sensors, and empowering them with methods of resistance best suited to them.

One of the first moves of the project was to coordinate a network event with partners from both academia and the children’s media industry, in order to surface perspectives on the issues, and agree priorities for forthcoming research. Included were academics, members from Dubit, Gluck Workshops, BBC and Tech Will Save Us. Following this and a literature review, two co-design workshops were developed. These involved friendship pairs of 24 8-12 year olds (12 pairs), each pair being assigned one of 4 technologies. Technologies selected were frequently used by the children and contained an array of sensors, and included smart speakers (e.g., Amazon Alexa or Echo Dot), phones/tablets, smart watches or other wearable smart devices, and the Nintendo Switch.

The first workshop’s function was primarily to understand what the children knew, or thought they knew, about digital sensors. Although some children recognised certain devices had sensing capabilities where the device’s interface or function made this clear (e.g., fingerprint recognition to unlock a phone), there were many blind spots regarding most sensors and knowledge of wider inferences they might make, and their surveillance capabilities. Many gaps in knowledge of sensors’ inner workings were also filled in with magical thinking, ‘a paradoxical “intuition”, where a child assumes events and conditions occur purely as a result of their own actions or thoughts, rather than looking for causes within external systems’ (Piaget, 1929). This magical thinking is further exacerbated by technological design, which is often based on a seamless and highly personalised user experience. Children often turned to the devices themselves when questioning the inner workings, using search engines or directly querying a smart speaker. Rather than use this opportunity to educate, the technology was instead further obscured with fantastical answers. In answer to one child’s question ‘Can I see you?’, Amazon’s Alexa responded, ‘I don’t have a body, I’ve ascended to the astral plane.’

Also notable was a general trust in digital products and a lack of concern about surveillance. CCTV in schools was almost unanimously considered a great way to catch naughty children and keep bad people away. The children often didn’t see a point in confusing or bypassing sensors, and were more concerned that such efforts might prevent the devices from operating correctly.

The first workshop’s outcomes affected the second workshop, which was redesigned to frame sensor disruption through specific challenges. A craft kit was sent to the children, and tasks included could be finding ways to skip on a Nintendo Switch without moving the joysticks, or to say a wake word without triggering the Alexa, for instance. The craft kits were very successful, and the children enjoyed them and created both fantastical and radical responses. The workshop also incorporated cross sections to help illuminate device’s inner workings (as is done in showing the inner workings of the human body, or mechanics). Many children imagined rather analogue configurations, with various wires and moving parts. Unlike many analogue devices however, and instead in line with technology companies’ frictionless user interfaces (and the fantastical responses of Alexa), the devices conceal their inner workings with unintelligible, concealed and static PCB boards and chips. The biggest takeaway from the workshops was that what’s needed is raised awareness in children of how sensors and data collection takes place, and why this matters with a critical view towards issues of surveillance.

In collaboration with students at RCA, the project was going to physically design practical implementations of the children’s responses, to be tested in schools. Due to COVID and with the workshop findings in mind, these designs were made digitally on a website, with an educational focus on issues around sensors. Tests were done online via Zoom with 20 children in Halifax and Glasgow, via the website, where children could interact with proposals of tools, and learn about sensors and surveillance. The face-to-face qualitative data from these sessions was rigorous and also aligned with the project’s ethical concerns of maintaining the child’s voice in issues that concern them.

Whilst this project focuses on methods for awareness-raising and resistance in children towards sensors and surveillance, it’s important to recognise that the responsibility for ethical collection and use of data ought to be with technology companies and policy makers first and foremost, and then there are also parents/carers. Building regulatory and legal frameworks and researching parent’s attitudes towards digital sensing are two more strings to our bow. Such approaches are addressed in McStay and Rosner’s previous project, also funded by HDI Network+, Rights of Childhood: Affective Computing and Data Protection, which went on to inform UNICEF’S Policy Guidance on AI for Children.

But, through a method of resistance that directly and immediately empowers users to disable or dirty sensor feeds, Countermeasures tests technology companies to rethink the user options made visible and legible in designs, and to readdress power imbalances and responsible use of data.

We will be posting the published report for this project shortly.

References

Piaget, J., & Valsinen, J. (2017). The child’s conception of physical causality. Routledge.

‘Zoom Obscura: Creative Interventions for a Data Ethics of Video Conferencing Beyond Encryption‘, Pip Thornton (University of Edinburgh), et al.

Contemporary data-driven systems are not, largely, designed with notions of human agency or data legibility at their forefront. As the application of these systems become more ubiquitous in social and economic spheres, we need to ask what human agency in those spheres looks like in a technical system. The translation of nuanced social problems such as consent manifest themselves in reductive mechanisms such as check boxes, which obscures information such as whether the individual was capable of consenting, whether they were pressured, or whether they understood the implications of sharing their data. The inability to contest decisions made by these systems can also reinforce power asymmetries built into algorithmic processes. If we cannot contest, how can we instead make visible inequities in design that limit human agency?

In response to our Ethics and Data theme callout, Pip Thornton (University of Edinburgh) et al’s project Zoom Obscura aims to lend agency to users of newly ubiquitous video conferencing technologies such as Zoom. Working within these online spaces themselves, Zoom Obscura maintains peoples’ ability to participate and negotiate their presence in these spaces, whilst also revealing the power asymmetries in the system’s design.

Artistic interventions can be a powerful way to capture public imagination on otherwise seemingly distant and detached concepts, such as machine learning and data driven systems. Zoom Obscura commissioned 7 artists to intervene creatively and critically to the dynamics, ethics and economics of video-calling technologies. The artists also took part in a series of workshops covering ideation, prototyping and presentation of their interventions.

Artists and Works

Martin Disley, How They Met Themselves

A bespoke software tool called Deepfake Doppelgänger was developed, taking advantage of the differences in algorithmic and human schemas of facial recognition. The tool generates a bespoke avatar that preserves the human likeness of the user, whilst obscuring the biometric data that would link the avatar to them.

Paul O’Neill, For Ruth and Violette

Based on a code-poem used by intelligence operatives in the Second World War, For Ruth & Violette plays with poetry and encryption to subvert Zoom’s communication infrastructures, whilst engaging with the complex history of obfuscation in relation to covert broadcasting methods.

ZOOM mod-Pack is a series of webcam modifiers run through a virtual camera which enable users to customise how they enter and exit a Zoom box and to play with distance, challenging the otherwise front row visibility of the 2D video chat experience.

Ilse Pouwels, Masquerade Call: Expression through Privacy

Ilse used emoticon “face-masks” as a bottom-up approach of dirtying data feeds, whilst staying understandable to humans.

Andrea Zavala Folache, How to touch through the screen, Erotics of discontinuity

Invites users to follow a choreographic score through an audio file, that becomes a guide to opening the possibility of giving and receiving touch through Zoom.

Foxdog Studios, Itsnotreally.me

Through the medium of a comedy sketch, itsnotreally.me shows users to how record video loops of themselves, that can be used to fake your presence on a video call.

Michael Baldwin, Group Dialogues

Participants enter into conversation mediated via visual and sonic cues, exploring latency and the processes of communication and control embedded in video conferencing technologies.

The artworks have been showcased at following events:

· Tinderbox Playaway Games Festival – Zoom Obscura works-in-progress online showcase (Feb-Mar 2021). Recording here.

· Zoom Obscura Launchpad Lab online event hosted by Creative Informatics, UoE (April 2021).

· Zoom Obscura exhibition, Inspace City Screens, Edinburgh – physical exhibition of artworks (June 2021). Video here.

· Open Data Institute (ODI) Summit, online (November 2021) – all artworks were shown as part of the Data as Culture art stream.

Dissemination of Zoom Obscura

Dwyer, A, et al. (2021), How to Zoom Obscura (instructional document)

Thornton, P. (2021) ‘Data Obscura: Creative Interventions in Digital Capitalism’. Invited talk at Newcastle University, October 2021

Dwyer, Boddington & Thornton, ‘Bodies of Data/Who owns us?’ Roundtable in conversation with Hannah Redler Hawes at ODI Summit (November 2021)

Future Publications

Elsden, Duggan, Dwyer & Thornton (2022), ‘Zoom Obscura: Counterfunctional Design for Video-Conferencing’, ACM CHI2022 conference on human factors in computing systems (accepted)

Thornton, Duggan, Dwyer & Elsden, ‘Privacy beyond encryption: creative interventions in spaces of digital capitalism’, Big Data & Society (in progress)

‘Data and Disadvantage: Taking a Regional Approach Towards Human Data Interaction (HDI) to Inform Local and National Digital Skills Policies‘, Professor Sarah Hayes (University of Wolverhampton), et al.

After exchanging ideas at our HDI Network+ workshop on ‘Human Data Interaction: The Future of Learning, Skills and Social Justice’ back in February 2020, Prof Sarah Hayes, Dr Stuart Connor and Matt Johnson in the Education Observatory at Wolverhampton University identified a deficit of HDI concerns in regional plans for digital up-skilling in the Black Country. Matt, Sarah and Stuart put together a plan to develop a cross-sector dialogue to begin surfacing and addressing these HDI concerns both regionally and also further afield.

Aimed at tackling disadvantage, the Black Country Digital Skills Plan has a supply and demand focus, teaching learners employable digital skills. Within this approach is the assumption that this kind of digital up-skilling is beneficial to all, and the personal and varied ‘post-digital’ contexts of individual learners are rather concealed (there are also broader, social and material concerns too, one in five people in the West Midlands do not use the Internet, for instance). In a plan aimed at tackling disadvantage, it is vital that training gives learners digital agency, or else those who are already marginalised may simply experience further disadvantage in the future. The HDI tenets of legibility, negotiability and agency can help within such plans to empower learners with digital skills that equip them to recognise surveillance and data gathering mechanisms, inform them about data sharing, and also algorithmic biases that may be enacting upon them or others.

Stuart, Sarah and Matt devised two seminars, a World Café style event and later a ‘What if Situation Room’, and invited various stakeholders of the Black Country Digital Skills Plan and West Midlands Digital Roadmap to join. Stakeholders included regional policy makers, digital businesses, local intelligence agencies, schools, colleges, digital skills providers, chamber of commerce, charities, researchers and local councils.

The first event was aimed at surfacing issues around digital inclusion. What was important for this project was to surface the real demands of stakeholders first, and then to see if and how HDI theory could integrate with those practical and situated concerns, as opposed to presenting people with abstracted approaches. Stakeholder concerns were initially centred around adding regional value through investment and creating the skills necessary for this. There was however a mismatch between these concerns and people’s access to resources, highlighted particularly by COVID-19, and a plethora of groups had already formed from the local council and other charities, with more democratic concerns around data poverty and other digital inclusion issues. One such agency, the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA) became more aware of the need for a digital inclusion coalition, and subsequently invited Sarah and Stuart to join them in forums and to participate in six regional bids focused on local regeneration, digital and data poverty, and inclusion.

The ‘What if Situation Room’ event introduced HDI concepts, and the importance of training that enables people to exhibit agency, negotiability and legibility within digital landscapes, as part of the stakeholder concerns that emerged from the World Café event. Challenges and opportunities for policy makers, practitioners and service users were then demonstrated and worked through. The key theme that emerged, whether stakeholder concerns veered economically or socially, was the human dimension of HDI, that it had to be built around relationships and trust in order to work. As this project moves forward, questions around what trust looks like in a post-digital landscape, and what powers and politics are at play, are central in building long lasting relationships, and in integrating HDI with groups concerned with digital up-skilling and inclusion. For more on this, see this recent paper by Sarah et al.

The event led to Policy Briefs for publication on Wolverhampton Council’s Digital Wolves site. Sarah and Stuart also presented their findings at the Institute of Education (IoE) Annual Conference, University of Wolverhampton in June 2021. Findings from the project were also included in the Black Country Insight Report (2021) published by Education Observatory.

As this project has evolved, it has become clear that more important than building a static framework or set of recommendations, is the building of cross-sector dialogue and relationships between regional groups across the UK, and internationally. This network weaving has become an emergent focus of the project, fostering sharing of knowledge and ideas, and helping to build a more robust and sustainable movement for HDI approaches in digital up-skilling and inclusion. Sarah has been able to join events convened by the EPSRC funded Centre for Digital Citizens (CDC). As a consequence, the CDC Agelessness Group supported a recent Collaboration of Humanities and Social Sciences in Europe (CHANSE) bid with five European partners. Wolverhampton Council also supported this bid and provided a testimonial too for the project leads’ Research Excellence Framework Impact Case Study. The contacts made and the cross-sector dialogue that has developed from the HDI research has led to Education Observatory being named as evaluators in 3 successful Community Renewal Fund digital inclusion bids submitted by a national charity. The West Midlands Combined Universities (WMCU) has also invited them to participate in a forthcoming regional summit on actions towards more equitable digital communities.

Owing to the project’s aforementioned approach of firstly unearthing stakeholder concerns, the discussion of HDI approaches is now widening to various sectors, in contexts where stakeholders are actually keen to act. In this way, the varying post-digital contexts of individuals and sectors form new test beds for thinking about and enacting HDI concepts, that may stretch beyond the purely digital into more positional social and material issues, where the tenets of legibility, negotiability and agency might morph depending on circumstances. Sarah’s recent book: Postdigital Positionality: Developing Powerful Inclusive Narratives for Learning, Teaching, Research and Policy in Higher Education examines some related changes that policymakers in education, and more widely, will need to address when seeking to further inclusivity agendas. The new Springer book (funded by our HDI ‘Theory’ theme call and building on what we have learned) will bring together cross-sector arguments and views from varying disciplines and contexts, including a focus on big data, data and local businesses, educational apps, IoT, mental health, social inequality, e-governance and optometry, and builds a living framework for the HDI tenets of legibility, negotiability and agency (and the emerging fourth tenet surfaced in our ‘Resistance’ theme). This cross-sector networked form of dialogue and governance is exciting new ground for HDI concepts, and is revealing the need for broader, more collaborative forums, or even a consortium on HDI. As this work grows, there is potential to broaden the scope further, building on international dialogues with interested groups and individuals in Croatia, Australia, Lebanon, Palestine, Norway and Hong Kong.

Links and upcoming Events

A recent paper by the project investigators, ‘Connecting Cross‑sector Community Voices: Data, Disadvantage, and Postdigital Inclusion’

A recent review of Postdigital Positionality, Brill

An open call for chapter contributions to the upcoming book

An upcoming event Cross-sector colloquium on Extending Human Data Interaction (HDI) theory, aimed at developing cross-sector contributions to the book. 10am – 12pm, 16th November, 2021

HDI project write up on Education Observatory site

Black Country Education Insight Report – a section on the findings from this HDI project

An upcoming event where Sarah will talk about this project and the forthcoming HDI book – 8th December, 2021

HDI Theory Project, Education Observatory

‘MIRLCAuto: A Virtual Agent for Music Information Retrieval in Live Coding‘, Dr Anna Xambó Sedó (De Montfort University)

Led by Prof. Atau Tanaka, our Art, Music, and Culture theme explores advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) techniques for composition, performance, and broadcasting. Our tenets of legibility, negotiability and agency now address tensions between the personal realm of human creativity and system autonomy.

Dr Anna Xambó’s (MTI2/De Montfort University, and in partnership with IKLECTIK, Leicester Hackspace, l’ull cec and Phonos) project MIRLCAuto: A Virtual Agent for Music Information Retrieval in Live Coding, approaches these tensions by way of a virtual agent (VA), that learns from human live coders in the uniquely personal yet public setting of musical performance. The VA aims to go beyond the more traditional ML approach of following live coder actions (call-response strategy), to create legible and negotiable actions.

MIRLCAuto also integrates ML algorithms with music information retrieval (MIR) techniques, in order to retrieve large datasets of crowd-sourced sounds. The project also points out how creative industries can benefit from using crowd-sourced databases of sounds in music creation.

In live coding, it is expected that the performer’s screen is projected to show the code and avoid obscurantism. This project emphasises the legibility of the code so that it is clear at all times the processes and decisions taken by both the VA and also the human live coder. A human-readable live coding language was developed for the project, and is shown in the code editor, providing communication messages with the VA in the console. In this way, a performer is able to understand how their personal data is being processed, and has agency to interact with the VA to help control the music’s direction.

The overall research methods of this project include rapid prototyping and participatory design techniques, allowing negotiability between the live coding community and the MIRLCAuto’s developers. To explore these methods, co-design workshops and concerts were organised to test the tool and receive continuous feedback. This on-going conversation has informed and keeps informing the development of the tool. This co-design process is showcased in this video where a new version of the tool is presented that includes feedback from the workshop participants:

Interactive Machine Learning (IML) incorporates a human-driven interaction between humans and machines that allows users to quickly generate ML models in an interactive setting using small datasets. As discussed in the NIME paper Live Coding with the Cloud and a Virtual Agent (Xambó et al. 2021), an important goal of the project is to enable live coders to train their own models. The system allows for designing a customisable VA to help live coders in their practice by learning from their preference within situated musical actions. MIRLCAuto takes inspiration from the IML approach, enabling training to be carried out via a series of processes integrated into the live coding workflow. The workshop participants have contributed to the tool’s design by proposing the integration of new methods suitable to their needs. Not only does an IML approach enable legibility, agency and negotiability with respect to MIRLCAuto, but it also enables the live coding community to understand the workings of, and create their own ML models to benefit their own musical performances.

Furthermore, by engaging with the three tenets of HDI, MIRLCAuto is a meaningful tool that goes beyond just personal use, finding a versatile solution to the nature of the live coding community, aligning with its open culture and DIY practices. It is also a way of bringing ML concepts to the live coding community, adapted to their respective live coding environments. This is just the beginning of a promising area of research and practice, which also has potential to be transferred to other forms of both musical and non-musical personal data.

The integration of ML with MIR techniques also has promising potentials. In collaboration with the ERC funded FluCoMa team, Xambó has previously explored MIR which combines crowdsourced sounds with personal collections of sounds. This, combined with other personal data such as musical listening habits (data which is currently collected for commercial uses), could here result in a complex, reliable, and accurate musical tool that would allow for combining serendipity with control, which can be potentially beneficial for musical creativity.

As part of this project, musicians/creative coders Hernani Villaseñor, Ramon Casamajó, Iris Saladino and Iván Paz were asked to participate in experimenting with the MIRLCAuto companion agent. These artists’ interest in MIRLCAuto, and the interviews/performances that followed sprung from an online workshop at *virtual* Barcelona led by Xambó in collaboration with Sam Roig (l’ull cec). The workshop was organised together with l’ull cec and TOPLAP Barcelona.

The interviews and work-in-progress performances below formed a 4-part video series, Different Similar Sounds, published by Phonos, which led to the on-site concert Different Similar Sounds: “From Scratch”. The interviews are available in 3 languages: English, Spanish and Catalan.

Hernani Villaseñor

Hernani Villaseñor, a Mexican musician interested in sound, code and improvisation, presents a live coding session from scratch using MIRLCAuto

Ramon Casamajó

Ramon Casamajó, a musician and computer scientist, presents a live coding session using MIRLCAuto together with Tidal Cycles

Iris Saladino

Iris Saladino, Buenos Aires based creative coder and sound oriented, presents a live coding session focusing on MIRLCAuto’s ability to search and download crowdsourced sounds using tags

Iván Paz

Upcoming Events

28th September: Different Similar Sounds “From Scratch”: Ramon Casamajó, Iván Paz, Chigüire, Roger Pibernat. Online video premiere on the Phonos YouTube channel of a live coding evening with TOPLAP Barcelona members hosted by Phonos at Sala Aranyó, UPF, Barcelona on 29th April 2021.

1st October: Dirty Dialogues with Dirty Electronics Ensemble, Jon.Ogara, and Anna Xambó. Live album to be released by the Chicago netlabel pan y rosas.

15th October: Dirty Dialogues with Dirty Electronics Ensemble, Jon.Ogara, and Anna Xambó. Online video premiere on the MTI2 YouTube channel of the final concert of the MIRLCAuto project. The music improvisation was recorded on 17th May 2021 at PACE, De Montfort University, Leicester, and it was hosted by MTI2.

The latest updates can be followed on the project website.

‘Governing Philosophies in Technology Policy: Permissionless Innovation vs. the Precautionary Principle‘, Gilad Rosner (Internet Privacy Forum) and Vian Bakir (Bangor University)

Our IoT, System Design and the Law theme asks, ‘What are the implications posed by the Internet of Things (IoT) for HDI, data privacy, and the role of the human in contemporary data-driven and data-sharing environments?’

Attending to the hidden ideologies that often underpin technology policy and governance, is Gilad Rosner’s project, Governing Philosophies in Technology Policy: Permissionless Innovation vs. the Precautionary Principle.

The project explores how the three HDI tenets of legibility, agency and negotiability are amplified (or not) via two opposing governance and regulatory philosophies (one being ‘Permissionless Innovation’ and the other ‘the Precautionary Principle’). The project also exposes the relationships, politics, norms and values of the actors and institutions involved in the governance of IoT, AI and emerging technologies.

‘If we over-regulate, we lose future social benefits from innovation’ is a common phrase in both professional and governmental discourse on policymaking for technology, particularly in the US. This phrase seems intuitively reasonable, but it is not neutral. It pits state regulation against innovation, assuming that the state is too slow to keep up with technological change, that markets are better at regulating themselves than governments, and that markets will generally produce outcomes that benefit society. These assumptions form the bedrock of what can be termed Permissionless Innovation, ‘the notion that experimentation with new technologies should generally be permitted by default’. (Thierer, 2016). This philosophical standpoint is realized through active political discourse, and industry positions on IoT governance are of the view that concrete harms from technological innovation must be shown prior to regulation.

Through this philosophy, government regulation (or permission) is presented as an antagonist to innovation, and an inhibitor to freedom and organic, bottom-up solutions. Thus, the preference is for those wishing for regulation to show evidence that the technology is harmful. However, this is of course often not straightforward.

Let’s consider a context where unintended and unforeseen societal harms are in fact avoided from Permissionless Innovation’s counter-argument, The Precautionary Principle. In the case of environmental change, it is easy to see how ‘when there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation’ (United Nations Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992). Indeed, it is within the sphere of environmental regulation that the majority of academic and legal discussion of the principle takes place.

But what about the Precautionary Principle’s relevance to IoT, AI and other emerging technologies? In the case of Cambridge Analytica, 50,000,000 people had their data used in ways that violated the spirit of consent, against consumer expectations, in a fashion many would consider manipulative. Furthermore, the intended role of social online platforms was hijacked for the unintended uses of political campaigning. Surfacing here are political and market conditions which directly disfavour the legibility of algorithms and data relationships. What philosophy is befitting for this type of problem?

In one of the few papers that explore the alignment of the Precautionary Principle with privacy and data protection, researcher Luiz Costa noted its benefits. Costa points out how the Precautionary Principle avoids risk-taking without a larger public discussion, thereby involving citizens in a decision-making process that counterbalances asymmetric citizen-government and citizen-industry relations. Our agency as citizens interacting with IoT systems is currently determined by our capacity to act within technical or business relations. The policy environment (and its philosophical orientation) is therefore fundamental to our agency. Here, regulation can be seen as a tool to protect citizens, counteracting the power imbalance against governments and industry.

As Costa also points out, monetary compensations for damages that cover Permissionless Innovation when it goes wrong are often inadequate for IoT privacy and data protection, where many of the emerging dangers are both non-economic and irreparable. The stockpiling of emotional data that render our inner lives transparent, the collection of children’s data from toys (see McStay & Rosner, Emotional AI and Children: Ethics, Parents, Governance, also funded by HDI Network+), our subjection to commercial manipulation via data, the diminishment of private spaces, exacerbated socioeconomic inequality and surveillance capitalism are all emerging dangers of technological innovation.

The slowing down of technological deployment through a precautionary approach gives society the time it needs to negotiate the political and institutional relationships that govern how these products are offered, and to form the norms needed to manage the sensitive and revelatory outcomes of technological innovation.

Despite being enshrined in Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Precautionary Principle’s application to privacy, data protection and technology governance is very limited. By vigorously examining the benefits of a precautionary approach however, and relating it to the core HDI tenets, this project is seeking to improve information policymaking in service of human-centric principles and privacy values.

The project aims to build networks of researchers, professionals, data protection authorities and other stakeholders in order to launch an inquiry into the role and benefits of the Precautionary Principle in the policymaking of emerging technology, and how such an orientation supports the HDI tenets of agency, legibility and negotiability. Through discussing the opposing orientations of Permissionless Innovation and the Precautionary Principle, a collaboratively reached white paper will be published. Also to be laid is the foundation for future grant funding to hold a Transatlantic Symposium on the Precautionary Principle in Technology Policy, as well as building momentum to continue the network beyond the scope of this project.

Vian Bakir

Vian Bakir is Professor in Journalism and Political Communication at Bangor University, UK, and is a leading international scholar of technology and society with expertise in the impact of the digital age on strategic political communication, dataveillance and disinformation. Her books include: Intelligence Elites and Public Accountability (2018); Torture, Intelligence and Sousveillance in the War on Terror (2016); Sousveillance, Media and Strategic Political Communication (2010) and Communication in the Age of Suspicion (2007). She has been awarded grants on data governance and transparency from UK national research councils (ESRC, EPSRC AHRC and Innovate UK). She has advised UK national research councils (EPSRC, AHRC) on their major investments into digital citizenship, AI and governance; and the European Commission on its Horizon 2020 work programme on digital disinformation. Her work has helped parliaments understand the impact of dataveillance, microtargeting and disinformation (e.g. Electoral Matters Committee, Victoria, Australia; UK All Party Parliamentary Group on AI; UK House of Lords Select Committee on Democracy & Digital Technologies; UK Parliament Digital, Culture, Media & Sport Committee); trade unions on adapting to data surveillance (National Union of Journalists); and businesses on public perceptions of data use.

Gilad Rosner

Gilad Rosner is a data protection officer, privacy researcher and government advisor. Gilad’s work focuses on data protection, US & EU privacy regimes, digital identity management, and emerging technologies. His research has been used by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and the UK House of Commons Science & Technology Committee. He has been a featured expert on the BBC and other news outlets, and his 25-year IT career spans ID technologies, digital media, robotics and telecommunications. Gilad is a member of the UK Cabinet Office Privacy and Consumer Advisory Group, and a member of the Advisory Group of Experts convened to support the forthcoming review of the OECD Privacy Guidelines. He is a Visiting Researcher at the Horizon Digital Economy Research Institute, and has consulted on trust issues for the UK government’s identity assurance program, Verify.gov. Gilad was a policy advisor to a Wisconsin State Representative, contributing directly to legislation on law enforcement access to location data, access to digital assets upon death, and the collection of student biometrics. Gilad is founder of the non-profit IoT Privacy Forum, which produces research, guidance, and best practices to help industry and government lower privacy risk and innovate responsibly with connected devices, and he has recently completed pioneering research on the privacy and ethics of using emotional AI with children.

‘ExTRA-PPOLATE: (Explainable Therapy Related Annotations: Patient & Practitioner Oriented Learning Assisting Trust & Engagement)‘, Matt Rawsthorne & Jacob Andrews (MindTech) et al

Our Future of Mental Health theme has funded the ExTRA-PPOLATE project, which explores HDI approaches to the creation of an automatic coding tool that can help therapists improve their practice, and importantly, is trusted by stakeholders such as therapists and patients. The multidisciplinary research team includes Mat Rawsthorne and Jacob Andrews (Principal Investigators) from the NIHR Mindtech MedTech Co-operative, Sam Malins (Clinical Psychologist), Dan Hunt (Linguist) and Jeremie Clos (Computer Scientist) from Nottingham University, as well as Tahseen Jilani (Data Analyst) from Health Data Research UK and Yunfei Long (Computer Scientist and natural language processing specialist) from the University of Essex.

Sadly, the fallout from COVID-19 is expected to affect mental health for years to come. Large quantities of high quality therapy are going to be needed. This means carefully assessing therapy sessions’ effectiveness, whilst also thinking carefully about how therapists’ time is spent. Currently, therapy assessment is resource expensive, often requiring a second and more senior therapist in the room. This second therapist could instead be seeing another patient, and their presence can also alter the dynamic between the patient and their therapist. The ExTRA-PPOLATE tool offers to assist this problem using machine learning. As an augmented intelligence system, ExTRA-PPOLATE aims to help therapists assess their sessions and support decision making, identifying weak spots and suggesting ways to improve the sessions. The legibility of ExTRA-PPOLATE’s algorithm is also important to the research team, and the model offers insight to therapists on how it has reached decisions, allowing the therapist to make corrections.

In order to create the ExTRA-PPOLATE tool, natural language processing techniques were applied to therapy transcripts to identify features associated with different psychological processes in therapy. Features included sentence length, emotive words, sentence polarity and readability scores. To train the ExTRA-POLLATE tool, machine learning was then applied to the numbers generated from these techniques. ExTRA-PPOLATE can now be used to identify processes that are (or aren’t) happening in sessions, although further work is needed to validate the tool.

The involvement and engagement of therapists, patients and the public have been priorities for the ExTRA-PPOLATE team throughout the project. Two PPIE (Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement) members with lived experience of mental health difficulties have been involved since the project’s inception. Also involved are a PPRG (Patient and Practitioner Reference Group), made up of patients, carers, psychotherapists, therapy trainers and therapy managers. With the help of Matt Burton McFaul from Virtual Health Labs, the ExTRA-PPOLATE team has conducted three interactive online workshops with the PPRG, to help reflect on and reassess the project, specifically looking at issues of transparency and trust. These sessions have been crucial in informing the tool’s development and enabled the implementation of HDI approaches that increase stakeholders’ agency, legibility and negotiability capabilities around personal data, differentiating the project from approaches that are exclusively data-driven.

Key changes to the ExTRA-PPOLATE tool have been informed by the workshops. For example, patients and carers indicated that if therapists were to review each output for accuracy, the resultant codings would be subjective only to the therapists’ choices and professional biases, preventing any opportunities to negotiate and discuss interpretations of the output with patients. In addition, therapists thought it impractical to spend extra time reviewing the coding after seeing each patient. Thus, the system is now being approached as a tool to provide an indication of where therapists could improve, without them having to check each automatic coding.

Patients and carers also explained that they would like their own view of the system readout and would like to be able to review the processes occurring in their sessions together with therapists, to provide agency and enable negotiability in how therapists’ practice should be changed. Finally, patients suggested that a small part of a therapy session could be analysed together with patients, such that the patients had a better idea of what the system was doing, permitting them greater legibility.

The feedback from the workshops is thus showing a design trade-off between legibility of this system, and usability and practicality, when used by stakeholders. Tensions and frictions can emerge in clinical contexts where strong power dynamics are present, and limited resources may challenge patients’ agency. PPRG members stated that while patients should not be required to invest significant amounts of time to understand how their data is being used, there is still a requirement for them to be enabled to understand this, such that informed consent can be legitimately received and patients have negotiability in choosing whether they consented to the use of the system with their data or not.

Therapist members of the reference group explained that attempts to show the workings of the tool, here provided as short sentences describing the language features that have been used to predict the identified psychological process, do not inform action that can be taken by any stakeholder, and thus while increasing understanding of how the tool has identified particular processes, do not provide a practical purpose. Other explainability features of the system, including an indicator of which processes should be used more frequently within a psychotherapy session, and which less, were seen as more useful features by steering group members.

The project team are currently reviewing the output from these workshops to reflect on how best to move forward with the practical design of the system while moving away from traditional data-driven approaches. Our objective is to keep championing legibility, negotiability and agency for patients in future related projects that aim to improve therapeutic interventions and practices. For more on ExTRA-PPOLATE’s interface, from the second of these three workshops, see here.

If you want to know more about the project and have any questions, please feel free to email: jacob.andrews@nottingham.ac.uk

@RawsthorneMat

@JandrewsMT

@JeremieClos

@mynameisdanhunt

‘BREATHE – IoT in the Wild’, Professor Katharine Willis (University of Plymouth) et al.

The pandemic has imposed many obstacles that have needed innovative workarounds from those involved across our projects, in order to continue carrying out their cutting-edge research. There is one particular project in our second theme, Beyond ‘Smart Cities’, that we focus on for this showcase, because its deep entanglements with COVID-19, though a barrier to the project, also reveal its work to be ever more urgent. The project is BREATHE – IoT in the Wild by Katharine Willis (School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Plymouth), with RA Marcin Roszkowski, the Breathers support group, the ERDF-funded EPIC eHealth project, the Hi9 start-up, the South West IoT Network and the U. Edinburgh IoT Network

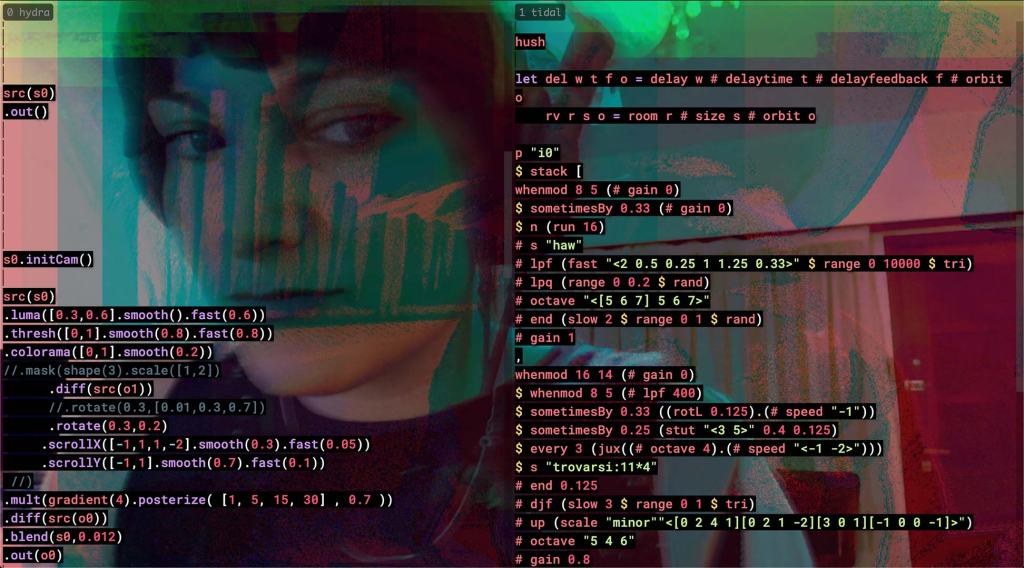

Taking place in isolated and rural communities in Cornwall, BREATHE aims to test the value of smart technology to people with health problems in those communities, to enable them to breathe more easily. Participants are given wearable blood oxygen readers, and are able to manage their own health data, facilitated by an IoT test bed network. Through this approach, the processes of data collection, sharing and assessment are put into the hands of the people the data concerns.

This project investigates the challenges of creating an IoT network in a low-connectivity, rural area, and also the potential of such a network for improving health outcomes for those living in more rural and isolated settings. The pandemic has both hindered and highlighted the need for these investigations.

At the beginning of 2020, BREATHE partnered with the Liskeard and Wadebridge Breathers support groups to cooperatively plan, conduct and assess fieldwork. Breathers is a patient–run group in which people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and similar long-term conditions, can get together to share experiences and take gentle exercise. Participating members were given pulse oximeters, and were asked to record their blood oxygen readings, alongside keeping a diary of readings and comments on their health. The next stage of the fieldwork had to be put on hold due to the COVID pandemic, as these vulnerable groups were required to shield.

Since March, the focus has been the technical development of prototyping a LoRAWAN IoT network, and linking it to the wearable blood oxygen readers, alongside an interactive speaker that people can speak to and get reports about their data from. Moving forward, the plan is to focus back into the community when the pandemic allows it, trialing a pilot of this IoT network ‘in the wild’ with the Breathers groups, alongside running a data ethics workshop.

Whilst the pandemic has hindered the follow up trial and community–driven aspect of the fieldwork, it has at the same time put breathing health, and the need for support networks, firmly on many organisations’ agendas, clarifying the necessity of this project.

An additional arm of this project is to assess its replication in isolated communities elsewhere in the UK, through partnership with U. Edinburgh’s IoT test bed network, working in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. As with Cornwall, this part of the project has also been encumbered by COVID-19.

However, as this project progresses in the midst of this pandemic, the ethical challenges it addresses are becoming more urgent. It matters how people access and share their data, especially highly personal data such as their health data, which can have large consequences if shared with commercial companies. Accessing personal data about breathing can also help self-awareness of the condition and allow data sharing with health professionals to help manage symptoms.

Traditionally, testing smart sensor networks ‘in the wild’ has not been widely undertaken, and this project seeks to create a model for data sharing, where people and communities share data to help both the individual, the group and more widely for the treatment of particular health conditions.

On a technical level, the project aims to demonstrate the benefits of IoT networks ‘in the wild’ with a view to new products and services being created, to innovate off-grid data sharing for health policy guidance on data ethics and truly benefit patients and people living with health conditions in rural and coastal communities.

We very much look forward to seeing this project progress, as it sheds light on the potential for improved health for those in rural communities, through applying HDI design principles.

Professor Katharine Willis

Professor Willis is Professor of Smart Cities and Communities and part of the Centre for Health Technology at the University of Plymouth. She leads on the UKRI-funded Centre for Health Technology Pop-up. Over the last two decades she has worked to understand how technology could support communities and contribute to better connections to space and place. Her recent research addresses issues of digital and social inclusion in smart cities, and aims to provide guidance as to how we can use digital connectivity to create smarter neighbourhoods.

‘Rights of Childhood: Affective Computing and Data Protection’, Prof A. McStay (Bangor University) and G. Rosner (IoT Privacy Forum

One of the first projects to come out of the AI Intelligibility and Public Trust call out is Prof A McStay’s (Bangor University) and G. Rosner’s (IoT Privacy Forum) report on Rights of Childhood: Affective Computing and Data Protection, which has already informed and been cited in UNICEF’s white paper Policy Guidance on AI for Children.

A relatively new form of artificial intelligence, Emotional AI in children’s toys is expected to become increasingly widespread in the next few years. Through measuring biometrics of a child (such as heart rate, facial expression, and vocal timbre) these ‘intelligent toys’ have potential to improve learning, detect and assist with developmental health problems, assist with family dynamics, help with behaviour regulation, and diversify entertainment. However, being placed at the heart of a vulnerable and delicate stage of life, it is critical that emotional AI and the legal frameworks surrounding them are legible and negotiable. They should provide children and parents with agency every step of the way, in order to prevent the exploitation of children (and their parents) via emotional data.

Using AI to assess and act upon the complex emotional and educational development of a child is no simple task, and with algorithmic complexity comes obscurity. We must ensure parents are equipped to understand the implications these systems and the data they harvest have. It is one thing to attend to a child’s emotional state in a playful or educational setting, but what happens when a child’s emotions inform content marketed to that same child? What happens when the turbulent emotional development of childhood is used to profile that person in later life, affecting chances of employment or insurance? The reductive nature of AI in a parental role is concerning too, as is the commercialisation of parenting and childhood more generally.

Alert to both the positive and negative potentials, this report sets out to explore the socio-technical terms by which emotional AI and related applications should be used in children’s toys. Based on interviews with experts from the emotional AI industry, policy, academia, education and child health, it is recognised that there are serious potential harms to the introduction of emotion and mood detection in children’s products. In addition, the report pays particular interest to the views of parents, and carries out UK surveys and focus groups (the latter with the help of Dr. Kate Armstrong and the Institute of Imagination in London). Through these, McStay and Rosner outline the necessary frameworks for emotional AI in toys. Problems and potential solutions discussed include the issue of current data protection and privacy law being very adult-focused, and not comprehensive enough to address child-focused emotional AI. The UN’s Convention on the Rights of the Child is also recommended as a valuable guide to the governance of children’s emotional AI technologies. It is also suggested that policymakers should consider a ban on using children’s emotion data to market to them or their parents.

In short, emotional AI design must be informed by good governance that reviews and adapts existing laws, and must be built around fairness to children, support for the nuanced roles of parenting, and care when involving AI in our early inner lives.

Read the full report and findings here.